In the World of Media, Who Watches the Watchdogs? Part 3

Is reporting without fear or favor still the operative paradigm for journalists?

Journalism is the watchdog, and journalists have a special responsibility to ask questions and hold not just everyone else, but also themselves to account. In fact, in order to remain credible, journalism especially needs to question itself.

But what’s happening now is that falling revenues are increasing the pressure on news organisations to attract followers. These organisations then need to ring-fence those followers, and that means keeping them happy by giving them what they want to hear, and not what they need to hear.

And nobody needs a watchdog to challenge that.

It’s well reported that this battle to increase market share by ring-fencing followers creates echo chambers: Like-minded people coming together in a place where there are no alternative voices. But this simply reinforces what they think they already know.

The big danger of this strategy is that in creating ring-fenced communities, you also create outsiders whose values and voices are not respected because they have no place in the echo chamber.

Inevitably, that means a second lower set of values is created for dealing with them.

That is exactly what has happened at the Guardian, they have everything to lose and nothing to gain from taking any notice of my complaint on their story about me, because my voice has no place in their echo chamber, and no place in their view of how the media world should work.

The Guardian code of conduct still pays lip service to its founding principles when it deals with the subject of fairness, writing: “The voice of opponents no less than of friends has a right to be heard . . . It is well be to be frank; it is even better to be fair.” (CP Scott, 1921).

He was the original editor and owner of what was then the Manchester Guardian, and to reinforce his message their style guide goes on “the more serious the criticism or allegations we are reporting, the greater the obligation to allow the subject the opportunity to respond”.

But my experience shows that this is only for those in the club, people immersed in the echo chamber that the Guardian thinks worthy of the process. As for the rest of us? As I have reported til now, well, we can write a letter to be considered for the letters page.

I have outlined in earlier stories here what my complaint was about, and in what ways it breached the Guardian code of conduct. But they refused to give me a voice in their echo chamber, or answer any questions for my report here about them, and it is this attitude from the paper that claims to hold the moral high ground that is destroying journalism more than anything.

It encourages a trend where the media no longer needs journalists, it only needs activists, all working together for a common goal of furthering their own agendas.

There is someone at the Guardian that is supposed to put the spotlight on very real problems like this. Yet in this case, Guardian media reporter Jim Waterson did not solve the problem, he was the problem. Of all the negatives I have detailed in previous stories, his role is arguably the most depressing and shocking.

Jim has a very special place in holding the media to account, he has a platform where he can hold court over what we do, and needs to be whiter than white, and in the words of CP Scott, in every criticism, ensure that the voice of opponents is also heard.

Buzzfeed, where Jim used to work for years, was very much about activism when it set up for business in the UK.

BuzzFeed’s dislike of the MailOnline was clear in a look at the UK team’s output at the time, with lists like ’21 Weirdly Angry MailOnline Commenters’. But there were many others, like “MailOnine photo caption fail”, “MailOnline comments about Angelina Jolies mestactomy”, “Anti Daily Mail signs appear on Britain’s railways”, “Weirdly angry MailOnline headlines” and “MailOnline Comments As Inspirational Posters.”

When Buzzfeed wrote any story that matched their agenda, such as the one about me that was really an attack on the MailOnline, they then set out on a campaign to ram the message home.

I guessed when they latched onto my story about euthanasia that it would also involve lobbying everyone else to do the same, and sure enough, shortly after Mark Di Stefano was in touch, Private Eye came next.

Fortunately, I had been working all day long on dealing with this matter and had already compiled our story, which although nobody used it, still meant I was well-equipped to provide a lengthy memo to the Eye, who decided not to follow it up.

But any hope that once again Buzzfeed lobbying would go nowhere was — this time — ill-founded when I discovered that the Guardian had covered it as well.

The Guardian is the paper to trust, by all accounts, Google favours it in search engine results. The Guardian saying that my story was wrong together with a repetition of the basic Buzzfeed claims that I ran a fake news factory were the closest thing to a stamp of approval Buzzfeed could have ever hoped for.

The reality is that we had a lot of reasons to justify what we did, but none of it was considered because it wasn’t requested by anyone at the Guardian. The failure to ask us for a comment meant the story was not balanced and goes against every rule, guideline and code of conduct in journalism, and it served up the perfect argument for the court considering my complaint against Buzzfeed to throw the whole thing out.

Even before the story Jim wrote about me repeating his former Buzzfeed colleague’s allegations, he had nailed his colours to the mast when he ignored news that I had started a project to support freelance journalism.

That’s because no one in the echo chamber wants to hear my voice, the only time I am allowed to appear there is when it’s to remind their followers why they don’t want to listen to me.

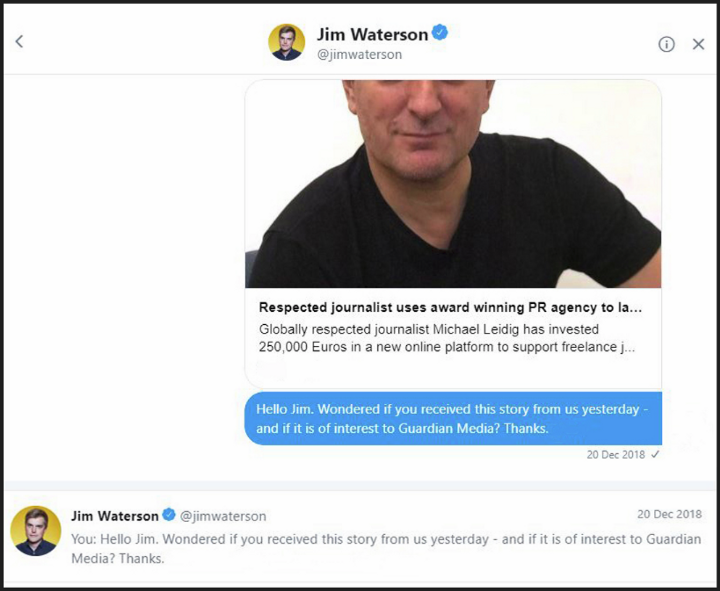

Two of the DMs sent to Jim Waterson asking for coverage of my business.

So this screenshot of two Direct Messages shows Jim seemingly ignored the positive, but he was happy to make allegations against us. As an outsider, my right to have a say is secondary. The last thing he’d want in that scenario is us knocking down his house of cards with a few facts.

I found it almost impossible at first to believe that he had not reached out to give me a say as Private Eye had, how had we missed his call, despite having a phone number on the stories that we sent to all UK news desks, and indeed on the very story Buzzfeed had hijacked and quoted from extensively.

I spoke in person to all my staff, and nobody at the office recalled getting any request from Waterson, especially given that we had so many things that we would like to have said. Still, not doubting that there must have been an approach, we decided to contact the Guardian to find out more.

On 6 June at 7 PM I wrote: “I was surprised and dismayed to read in your article concerning CEN’s reporting of the Dutch girl story that we failed to reply to reporters request for information. I have reviewed firm documents and spoken to colleagues and yet can’t find any record of the request.”

In reply, we were told that Waterson used the contact form on our homepage because there was no email address or phone number on the website.

I then replied: “The story has already gone around the world now anyway, but given the importance of an article being balanced and fair, should it not be standard practice at the Guardian to ensure that the other side has been contacted and given the opportunity to reply? We received no email, how do we know that your correspondent was not distracted and forgot to press send? For whatever reason, nothing turned up at this end, and the first I knew about your article was when it was published.

“When I am in the last stages of an investigation and in the process of giving the other side the opportunity to reply, I do not go ahead until I confirm that they have received it. That means that I insist on getting an email reply back, and if that fails, I make a call to a named person to let them know the email has been sent.”

I concluded: “My problem is this, the story has been published and it was not fair and balanced.”

I then, again, asked for a right of reply.

They wrote back, by which time it was 10th of June, to repeat that they had used the contact form and added: “You are at liberty to submit a letter for publication to the letters desk. However, please bear in mind that the decision on publication is a matter for the letters editor.”

In a different font they then pasted in what is obviously the standard reply to annoying people like myself saying: “The email address that team is on is guardian.letters@theguardian.com -” and so on.

On 17 June, I wrote them again saying: “I am very unhappy with the way this is being handled — would you consider IPSO arbitration on the matter? If not, what other independent professional body would you consider using? I have suffered financial loss as a result of the article because while it’s one thing for Buzzfeed who I’m in a legal battle with to say that we fake news, it’s quite another thing for the Guardian which is very well respected to repeat those claims.

“If not IPSO, what do you suggest?”

Another 24 hours later and as far as they’re concerned they made a “good-faith effort” to contact my news agency and that was that.

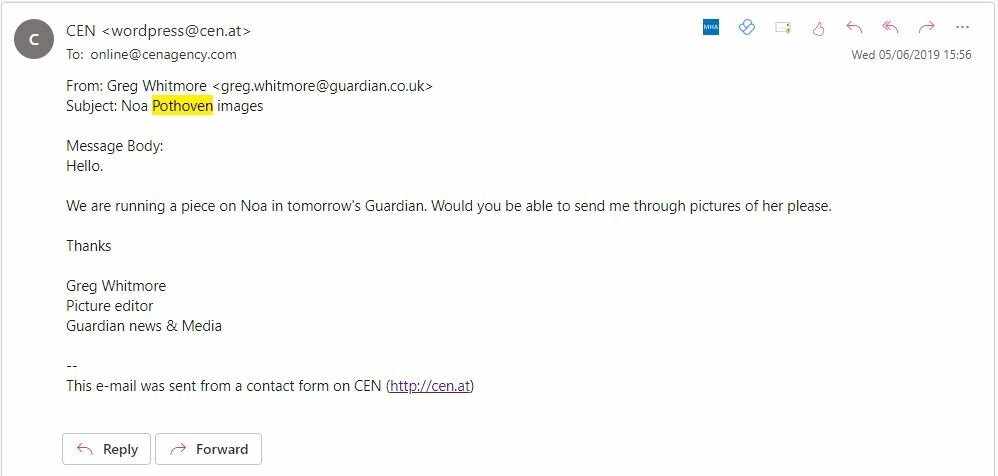

We know that the contact form worked, because we had a steady stream of requests, and in particular the Guardian picture desk contacted us the same day Waterson was supposed to have done to buy pictures for a news story.

We did not share those illustrations because the Guardian picture desk was blacklisted for failing to pay for previous work that we have provided.

But the point is that the Guardian picture desk had managed to contact us using the form, but Jim Waterston did not, and this article then ended up being used in the court case against us.

The Buzzfeed lawyers were able to use it in their submission, and so it was seen by the judge with no comment from us to redress the balance. The following is an extract from that they wrote, and you can easily imagine how it was perceived by the judge:

“The story caused an uproar about the Dutch government euthanizing a vulnerable minor until the girl’s grieving family revealed that she had committed suicide at home on her own, without state intervention. Simply put, it is rank hypocrisy for Plaintiffs, who continue to abuse press freedoms by callously profiting from fake news stories, to ask this Court to deprive BuzzFeed of their constitutional rights in order to stifle responsible reporting about CEN’s egregious conduct.”

It sounds great, but it was flawed like Buzzfeed’s own reporting. Nowhere did anybody say that Noa committed suicide. Sceptics might say that we chose to ignore Jim’s request and pretend it never arrived, and that’s a fair point.

But exactly because I had spent years fighting Buzzfeed, I had a much better than usual understanding of the burden of proof, and when the Guardian pointed out it was only my word that he had not contacted us, as the contact form offers no confirmation, we went to a London based data firm to help us get to the bottom of it.

I contacted them because everything that happens in the digital world is recorded somewhere, and sure enough, I discovered that a record existed of all the transactions on the contact page on our German server.

When I reached out to the German company, they told me that the data could only be kept for a certain amount of time, but the good news was that it was still there, although we only had 24 hours to get it.

The company I contacted specialises in harvesting data for presentations in court cases, they are completely independent and although one side or the other hires them, they guarantee with their reputation the integrity of the data they harvest, and provide guarantees in the way they harvest it that match judicial standards.

The company verified that the data confirmed the Guardian picture desk had contacted us, and we could see that there was a number of other requests made which we had also received and checked, but there was no other record at all of anyone attempting to reach us, and certainly no request from Jim Waterston, and that meant that he had not made one, exactly as we pointed out to the Guardian when we first wrote to them.

Either he had made a mistake, which would be the charitable interpretation, or maybe, just maybe, he had decided not to contact us.

Again, we wrote to the Guardian, this time from our lawyer.

He made it clear that we had used an independent firm to verify that no request be made, and referred to the lack of a right to apply as a “mistake”, with the main point being that it was now clear the article was not balanced and needed to be corrected.

Again they refused.

They wrote: “Our reporter Jim Waterson examined his internet history which showed that he accessed the CEN “contact us” page at 11.31.43 (British Summer Time) on Wednesday 5 June 2019, which would suggest that he pressed “submit” on the request for comment shortly thereafter.

“He assures me — on that basis and in those circumstances — that he made an attempt to contact CEN during working hours through the only contact route noted on their website.

“He provided me with a screen grab of the relevant internet history and I have no reason to doubt the good faith of this account.”

They continued: “On 10 June 2019, I indicated that he was at liberty to submit a letter for publication to our Letters Desk. I am not aware if he took up that suggestion.

“Nothing in your letter of 16 August gives me reason to change the decision which I conveyed to Mr Leidig more than three months ago. Accordingly as presently advised we consider the matter to be closed.”

That isn’t exactly the whole truth.

It completely ignores the fact that whatever she or Mr Waterston may claim, it was now 100 per cent fact that they had not used the form to contact us.

An independent assessment of the database had proven that no such request was made, which completely negated the fact that he happened to have looked at the webpage, which is not the same thing as sending a message to it.

Secondly, had I been offered the right to have a letter published I would have taken it — what they offered was that I could waste my time writing it and they would “consider it”. That is by a long chalk not the same thing.

A reply they had cut and pasted to the standard reply they used to fend of thousands of complainants made it clear that would probably be little chance of it ever being used. I simply didn’t have the time to waste on that, and nor did I have any faith that they were honest in making the offer.

Thirdly, the reason that we don’t have a number on our website is because it is listed together with an email at the top of all of our copy, and all of our clients will be able to access that content and get the number, it is also on all our pictures too.

Even Buzzfeed, when they were preparing their first exclusive about us, delayed publication for days because they did not get a reply. They sent emails, they telephoned, and they even sent recorded delivery letters.

There are extensive notes in the records they provided detailing their efforts to get a reply and what the best tactic was to get me to confess or even boast about my so-called fake news empire.

The Guardian did none of that, and their story should never have been published until the story was ready. Especially when writing something about somebody where you might be accused of bias, as in this case, it needs to be doubly checked.

Yet it’s one thing to demand standards from others, and another to live them yourselves.

I believe they had no interest at all in letting us put our side of the story. They were given more than enough evidence to show they had not given us the opportunity to reply to the extremely damaging criticism, and especially so as it was then used in a court case against us, backed up by the Guardian name, and written by a reporter that never made it clear his links to the people we were in a legal battle with.

As I wrote to my lawyer all at the time: “My problem with the BuzzFeed coverage this week is that once again it underlines that I don’t have any opportunity to put my side of it.

“We always attempt to do the best job we can and tackle the important stories, but on breaking news items in hindsight it is always possible to see how things could have been done better, but that’s the point, it’s always possible ‘in hindsight’.

“You could take apart any media reporting on any big subject and that is exactly what they’re doing, which is having a hugely negative effect on my business to the point now where it’s almost impossible to continue.

“People in the UK media newsrooms are reading all this negative reporting about how we made allegedly massive mistakes in an important story with no balance.

“The Guardian’s ex Buzzfeed staff (Waterson) member gave me no right to reply, I am not allowed to speak to BuzzFeed — with good reason — when they give me a right to reply, and then after that everybody just used the Guardian and to a lesser extent BuzzFeed as proof that we are an unreliable news organisation.

“I am not trying to stop the media from asking valid questions for legitimate investigations, but especially where there is a commercial advantage there needs to be balance, and there is no balance here.

“I wonder how many stories this would have generated in the Guardian media if it had involved the Mail online?”

In conclusion, it may seem an academic matter that the Guardian, like Buzzfeed, are not members of IPSO. Yet my story shows that when you suddenly end up on the wrong side of a Guardian report, you cannot rely on them to give you a fair hearing.

I would be happy to go to IPSO tomorrow if the Guardian were to agree, but we know that will never happen, because as far as my experience indicates, they have one rule for themselves, and one rule for others.

Journalist and editor Michael Leidig is the founder of NewsX Media, CEN Agency, Mediatech Support. Vice chairman of NAPA. Reporting without fear or favor.